I recently had the pleasure of inviting horror fiction legend Ramsey Campbell to an interview for the Plutonian. Let me start by saying that anyone who enjoys horror should run out and read his work immediately. To call Campbell a legend is almost an understatement. In my opinion, any list trying to figure out the greatest writers of horror has to include Campbell to be respected. Ramsey Campbell stands with the greats, the classic writers like Poe, Lovecraft, and Jackson, and the modern greats like Etchison, Ligotti, and Kiernan. In this interview, I ask questions that follow my own obsessions and interests in his work. This is not meant to be an interview for people new to horror or new to Campbell’s work. This is me getting to pick the brains of one of my favorite writers. If you are new to Campbell let me give a short list of recommended works:

Demons by Daylight

Cold Print

The Height of the Scream

Scared Stiff

Dark Companions

Ramsey Campbell, to me, is one of the great writers of unease. He also is, quietly, one of the great writers of transgression. His stories whisper, but in those whispers he explores taboos, diving deep into areas we as a society are not comfortable with. Perversion, obsession, the horrors of the body and its functions. The family as alien. Our secret desires for transformation and death. He writes masterfully in both subtle ghost stories and horrific tales of desire and breakdown. I hold Campbell's work dear to my heart, his work a dark beacon drawing us in, lovers of things macabre and perverse.

Plutonian: As opposed to what would probably be the majority of horror fiction, I feel one of the major themes in your work are stories that feature a protagonist who is maybe a bit sleazy, someone who has an obsession that some may label as perverted or kinky. Instead of the good guy, the kind mother, victimized by monstrous forces from beyond. They, throughout the story, seem to be seeking their doom, and when they find their weird doom, there is a sense of completion to their journey. Like that is what they were, maybe unknown to themselves, seeking all along. Instead of a hero's quest more a pervert's quest. Like for instance, in your short story, Cold Print, or some of the tales in your collection Scared Stiff. Also among that line, there is maybe a Hitchcockian trope of placing blame on the viewer/reader for wanting the outcome, which seems to be implied by you in some of these works. Blaming the reader for desiring the dark ending that has been delivered to them. What interests you in the pervert as protagonist? And this seeking of both protagonist and the reader of horror fiction for perversion and doom, what are your thoughts on this?

Campbell: Are there so many? I’d have said a handful among hundreds unless I’m overlooking some. Perhaps they exemplify my interest in psychological extremes of various kinds. Sam Strutt in “Cold Print” conflates a couple of gym masters at my old grammar school with a colleague in the Civil Service office where I had my first job (he did indeed plague me for “exciting books” when he learned I imported Olympia Press books and such, then banned in Britain). Was I taking a sly literary revenge (unusual for me) on some or all of them? You’re right about the Hitchcock similarity, an element Robin Wood’s great monograph on the director had made me aware of. It’s certainly Strutt’s search for forbidden texts that does for him, but then I used to obtain banned books too. While his fate has a certain relevance to him, I don’t think the tale suggests it’s proportionate to his transgressions, such as they are. For me horror, to be horror, needs to be undeserved, but perhaps that means the reader seeking horror wishes just that for the character. We may also feel the horror reader relishes the transgressive, and in the years of home video witch-hunting, the forbidden.

As for the others—well, it’s the partner of the protagonist in “The Other Woman” who suffers, not him. In “The Limits of Fantasy” the central character does end up with the tables turned on him, but then many people of the persuasion like to switch sometimes. In “Again” her kink keeps the revenant vital, and the straight man is the butt of the dark joke. Danny Swain’s fate in Incarnate is terrible enough, but less so than that of some of the characters more innocent than him. Perhaps the comic tale “Safe Words” makes my sympathy for my kinksters clearest, or else my introduction to Nikki Flynn’s Dances with Werewolves.

Plutonian: A lot of works in the horror field tend to try to convey a sort of voyeuristic sadism. A putting yourself in the position of the killer, enjoying the murderous body count, a sort of sick power fantasy. But in a lot of your works, I see an impulse to masochist submission to those dark outer forces. A wilful drowning into the dark and the obscure. In stories such as The Telephones or The Second Staircase, there seems to be a desire to be violated. Do you feel there is a masochistic tendency in some of your stories? Is there a sublimated desire for corruption and violation in your works?

Campbell: I certainly think it’s present in those tales, not even necessarily sublimated. Mind you, they were written in my late teens, which were really my extended adolescence. Like Fritz Leiber (make of that what you will), I was a late developer. My sense of sex, such as it was, derived very largely from reading (the same books I spoke earlier of importing) rather than from experience, and I suspect it was pretty inchoate. You mention placing the reader in the position of the killer. My fiction often has from The Face That Must Die onwards, but I think it generally presents such characters as fatally inadequate, committing their crimes in a bid (however unconscious) to impress themselves and their view of themselves on the world. That’s also true of my occultist figures, John Strong, Peter Grace (ironic names), and their kind.

Plutonian: Thomas Ligotti has talked about how H. P. Lovecraft dreamed the great dream of supernatural literature - to convey with the greatest possible intensity a vision of the universe as a kind of enchanting nightmare. After reading the best examples of horror fiction, the mystery is left unresolved, a lingering dread, or maybe a feeling of being unsettled, envelops the reader like a thick fog. But there is also a fascination, an enchanting allurement. Horror fiction, at its best, tries to imitate the ambiguous nature of nightmare. And of course the pleasures of nightmare. Evoking nightmare is no easy feat, if you go too fantastic you lose the realism necessary to truly unnerve the reader, yet if you are too ambiguous the work may lack the punch needed to affect the reader. It's not an easy path, bringing the reader through realism to nightmare. Of course a story, a work of fiction is too self-conscious to ever be pure nightmare. How does a horror writer try to convey this enchanting nightmare? Have you tried methods to remove yourself from your work and let more unconscious impulses reveal themselves, maybe to try to get the piece to be more akin to pure nightmare? And why are nightmares so pleasurable, so enchanting, for those of us so inclined to desire the experience?

Campbell: I relish actual nightmares—free surrealist films, as I tend to think of them. Jenny knows not to wake me up even if I’m emitting uneasy sounds, because I believe nightmares have their own built-in release mechanism and will set you free if they become too terrifying. On the whole, they have. That said, I’ve recently had a couple of unnerving experiences. One recurring motif in my dreams over the past few years is that my phone goes wrong. Twice now I’ve dreamed it did and then realized this means I’m dreaming, only to fear that I won’t be able to escape the dream. Last time I started shrieking “I’m dreaming” to waken myself and eventually did, but when I told Jenny about it I realized I hadn’t wakened after all. Maybe I’m still trying to do so.

Evoking them in fiction—I think the only way to do that is to follow my instincts. Conscious striving doesn’t work. The Grin of the Dark is one result of that approach—of liberating my imagination as much as I can and trusting it to lead—and recently “A Life in Nightmares” was another attempt. By far the closest I’ve ever come to having a pure nightmare straight onto the page was Needing Ghosts. A few days into writing the first draft I came to the scene at the bus terminal and was disconcerted by how much odder the destination names were than I’d planned. What to do? I elected to see what might develop, and until the story was completed I found myself hurrying to my desk each morning to discover what the day’s events might be and transcribing them, or so it seemed, direct from my subconscious and barely keeping up with their impetus. I may say that although I believe in rewriting as ruthlessly as possible, I changed that first draft hardly at all for publication. For once I didn’t see the need.

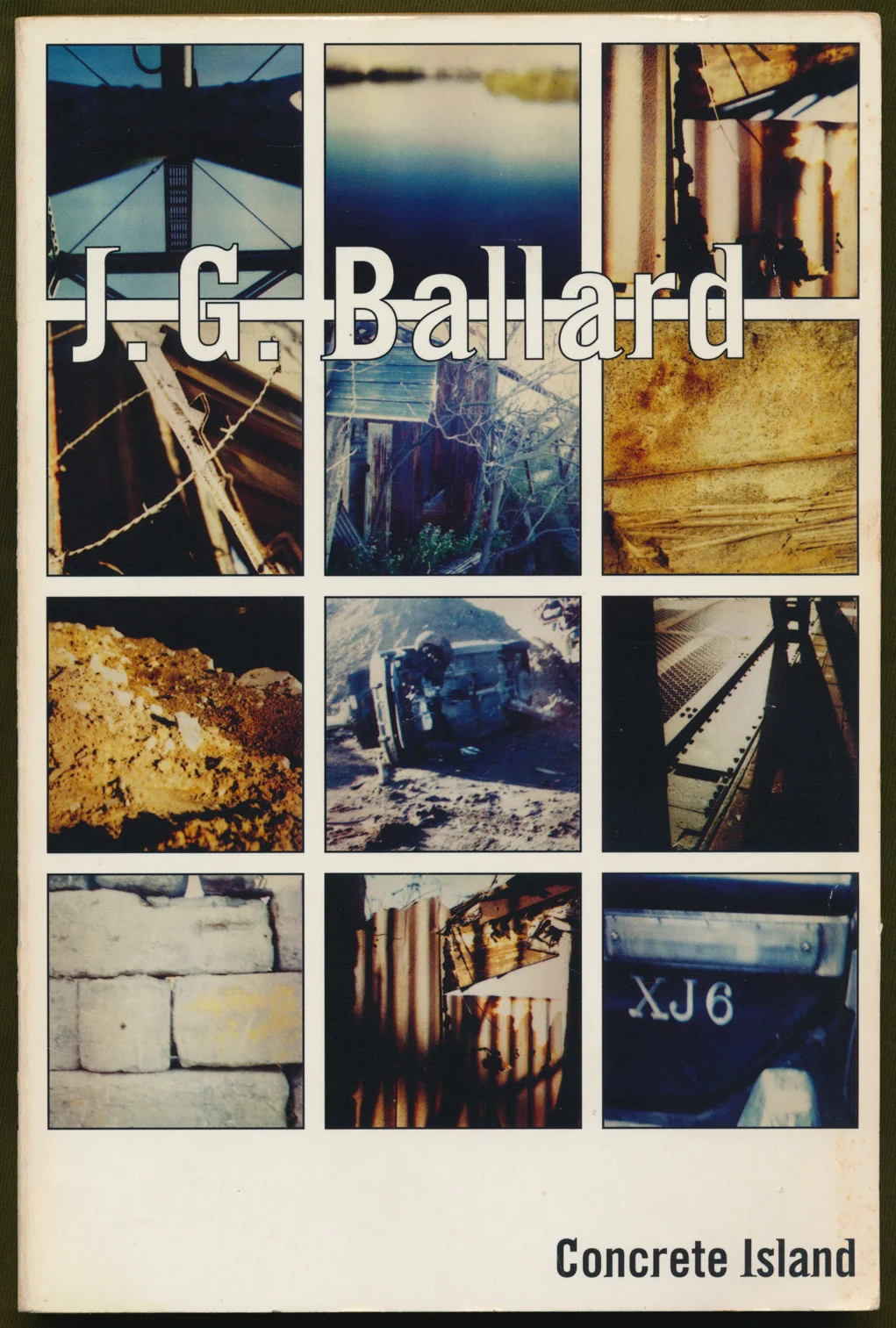

Plutonian: Writers like Lovecraft and Leiber are well-known influences on your fiction. But I would like to ask about maybe more subtle or less talked about influences. I would like to ask about the possible influence of the writers Alain Robbe-Grillet and J. G. Ballard on your work. Grillet pushed abstraction and eroticism into the mystery genre in works like The Erasers and The Voyeur and Ballard moved those into the science fiction genre in works like Crash and The Atrocity Exhibition, and I feel that one of your innovations was threading abstraction and a perverse eroticism into the horror genre. Most strongly in your collections The Height of the Scream and Scared Stiff for instance. I have read you briefly talk about both authors in interviews and I was wondering if you could speak on them a little bit more, were they direct influences and how do you see their work relating to yours?

Campbell: Not so much Robbe-Grillet directly as through Resnais’ film Last Year at Marienbad, an enduring favourite of mine. This and his subsequent film Muriel encouraged me to elide transitions in the narrative, especially temporal, most radically in the final version of “Concussion”, where I had flashbacks occur in the middle of a sentence—an attempt to produce the same sense of dislocation the films did. Ballard could well be at the root of some of my stories where solitary protagonists wander urban landscapes that may embody their psychology or indeed subsume it. I think either writer might loom behind my tale “A Street was Chosen”, told entirely in the passive voice with characters identified only by symbols. I once thought of writing a story in the form of an index to a nonexistent book, but found that Ballard had. Incidentally, I think we’re now living in a world he might well have hoped only to imagine.

Plutonian: Most critics and serious readers of horror fiction would point to your early collection Demons by Daylight to be a masterpiece and a turning point in the history of the literature of horror. I have read that the table of contents for that collection had been revised at least once if not a couple times before its release. I believe that The Cellars and also Before the Storm were both strongly considered to be included in Demons by Daylight? I was hoping you could talk on what stories were almost to be included in that landmark collection. And has there ever been any talk of releasing an expanded edition of Demons by Daylight including those works that almost were included?#

Campbell: Well, thank you very much! “The Cellars” might have gone in if Derleth hadn’t taken it for inclusion in his anthology Travellers by Night, but “Before the Storm” never would have, since I didn’t think it up to scratch. Indeed, when he asked me for a contribution to Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos I mentioned that I had one that wasn’t worth his attention, or words to that effect; that was the tale in question. (Instead, I sent “Cold Print”, not really expecting it to find favour, and was surprised it did.) The stories Demons would have included were “The Scar”, “Reply Guaranteed” and “Napier Court”. Just now we’re working on a limited edition that will indeed include them all, together with the first drafts of all the tales that were substantially rewritten.

Plutonian: I know you are a great fan and critic of horror cinema. I personally believe we are experiencing a new golden age of horror cinema. Films like Hadzihalilovic’s Evolution and Escalante’s The Untamed to me are new classics. Also, recent films that are blazing new trails are Robert Morgan’s film Stopmotion and Oz Perkins’s Longlegs. Themes that this new horror cinema seems to explore are a loss of a sense of reality among people, the taking over of simulated realities or dream realities more and more into our lives, the unease and distrust of one's own body, the physical self as alien to us, and an explosion of a corrupted sense of desire and sexuality. What are your thoughts on this new wave of horror cinema? How would you say horror cinema has evolved into its current form? And what importance does horror cinema have in our world today?

Campbell: I’m impressed by the range of unconventional, even groundbreaking, films the field has brought us of late. Besides the titles you cite I’d include Beau is Afraid (the best comedy of paranoia I’ve ever seen) and Christian Tafdrup’s ruthlessly devastating Speak No Evil. Many contemporary horror films seem willing to shine a strange but searching illumination on our world and aspects of it, though I’m resistant to those films that declare their metaphorical significance too openly. Certainly makers of horror films these days often seem more conscious of their themes than was the case in the past, which may be a mixed blessing, if it saps instinctive creativity—for me, the most fruitful kind.

Plutonian: From Lovecraft pastiches to abstract and ambiguous tales of unease to erotic body horror to nightmare comedy, your work has always been innovative and vital. What is next for your work? Is there any news on new works? What interests you to write after such a long and accomplished career? What can we look forward to?

Campbell: Next up is a new novel, An Echo of Children, central to which is my belief that the attempted exorcism of children is a form of child abuse, dangerous and far too often fatal. All the same, you may find an uncanny element in the book. My notebooks are still swarming with ideas, and I’ll develop as many as I can while I’m capable. I hope I can still surprise us—me and the reader. One of my recent books might: Six Stooges and Counting, a personal appreciation of the Three Stooges. Did you know Kubrick’s film of The Shining was an extended tribute to them? Look within for the evidence, and more: the Stooges as the witches in Macbeth, the misleading trailer as an art form, the Stooges as a kind of gestalt whose identities constantly shift…