Out of the darkness, the image of an eye, so close to the lens and so deeply shadowed that it’s almost an abstraction, staring directly at the viewer. Cut: we now directly face onto the camera lens itself, a startling reversal, its round black lens an impassive mirror to the round black pupil of the previous image. A series of subsequent close-ups, each fading out from black, present us with isolated, fetishistically observed details of mortified flesh: bound feet, bound hands, a young bloodied face. All this observed and photographed by a large, middle-aged man who gazes upon this tortured boy—we see now that it is a boy, and furthermore a child, no older than ten—with an obscure mixture of wonder, erotic fascination, and stony despair. After photographing him, the man comes near the child’s face, lecherously presses his lips close to the corner of the mouth in a cold, sidelong kiss. He staggers back, and, almost as if he’s ashamed, wipes the trace of the kiss from his lips with a handkerchief, all the while regarding the boy’s bruised shoulder blades as he dangles from the rafters. Sighing, he contemplates the scene deeply for a moment, and then, steeling himself for the work he has yet to do, slowly lifts a wooden plank from the floor, raises it, and, for once mercifully off-camera, murders the boy by clubbing him once, sharply, in the back of the head. In the following moments, he will proceed to attempt suicide by leaping from the roof of the building. At the same time, everything described has been observed not only by the audience but by an unseen voyeur, their presence implied by shaky P.O.V. handheld camerawork and the quick panting of their breath on the soundtrack, who sneaks into the basement chamber and collects the murderer’s ghastly notebooks from the floor.

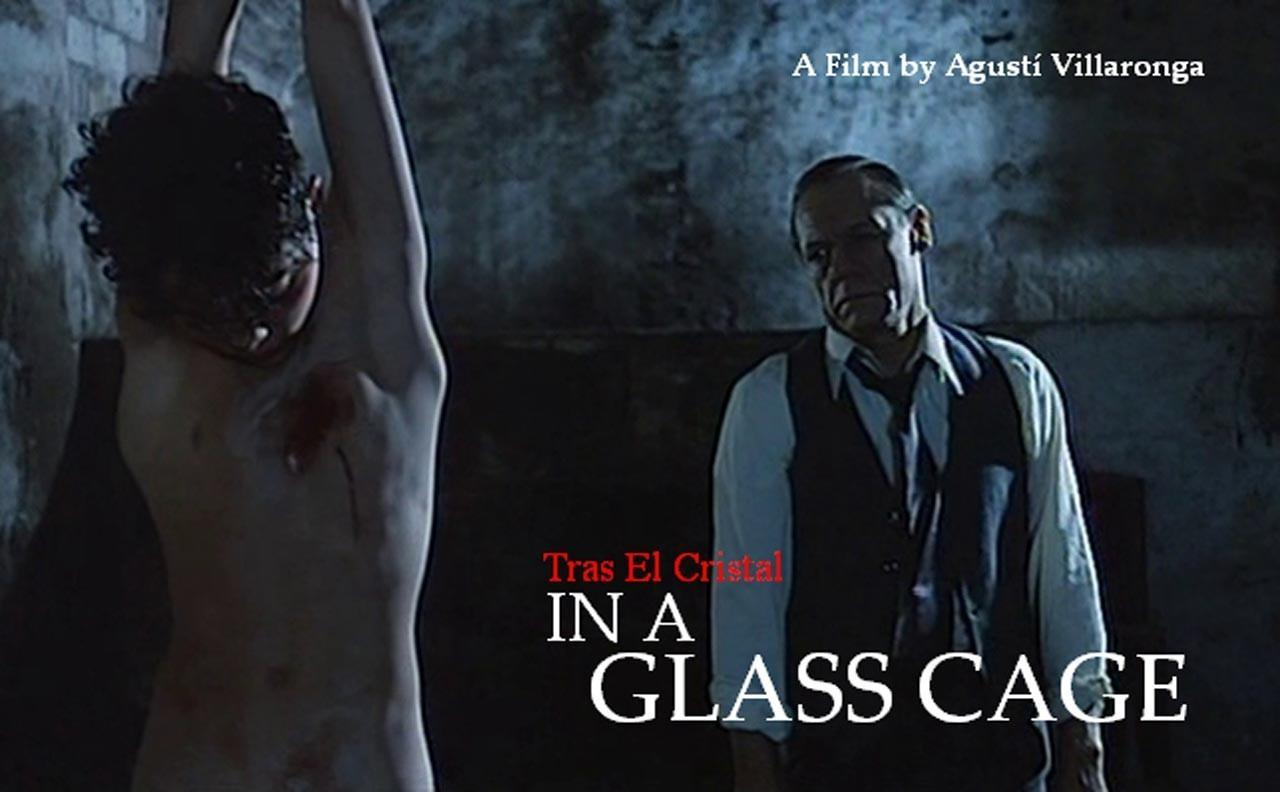

The opening scene of Agustí Villaronga’s 1986 horror film In a Glass Cage presents images and implications that most viewers will find so repellant as to be almost unwatchable. After all, these subjects—suicide, sadism, pedophilic desire, and especially violence against children—remain perhaps the most universally reviled taboos in our society. And yet, in a tight four-and-a-half-minute sequence, Villaronga confronts us with them all, and in uncommonly graphic detail. Not only are we shown the naked and degraded body of a young child, but we are literally forced to take the abuser’s perspective, the inaugural montage of bodily details directly replicating the erotic-sadistic-objectifying gaze of the killer. Our gaze is sutured to that of the perpetrator of violence (and, moreover, his unseen witness), actively encouraging us to partake in their bestial fascination.

This sequence succinctly establishes the whole formal and thematic edifice of In a Glass Cage, a film which, I think, has been often misrepresented by much of the non-academic writing that discusses it. The prevailing interpretation, as expressed in such writing, is that In a Glass Cage is an art-horror film about trauma, both individual (the sexual abuse of children) and historical (the atrocities of Nazism), and how it violently reproduces itself across generations. A surface-level examination of the narrative would certainly encourage this reading. The story tells of Klaus (Günter Meisner), an ex-Nazi and murderous pedophile, who, after the failed attempt at suicide at the climax of the opening sequence I’ve just described, finds himself almost completely paralyzed and dependant upon the respirations of an iron lung to live, which his frigid wife Griselda (the great Marisa Paredes, of Almodóvar fame) and their daughter Rena (Gisèle Echevarría) reluctantly undertake the management of. Some years later, a mysterious youth (David Sust) suddenly appears unbidden at the house, insisting that he serve as Klaus’ nurse. Gifted with the fortuitous name of Angelo and bearing a countenance comely and sinister in equal measure, Griselda is immediately suspicious of the new nurse, but Klaus insists they hire him after a private conversation between the two. It will come as no surprise that Angelo was the hidden voyeur at the start of the film, and, moreover, a victim of Klaus’ sexual violence in his youth. Having closed in upon his onetime abuser in a completely helpless and vulnerable state, he will proceed to sadistically reenact Klaus’ past crimes in front of him, torturing the monster of his childhood even as he gradually evolves into his mirror image.

This clever cross of Teorema and The Night Porter would appear to offer a very straightforward argument: violence is cyclical. The victims of violence can grow up to reperpetrate it. Trauma is passed on like some sort of genetic disease, an interminable merry-go-round of victims turned executioners, with no end in sight. This is a common enough theme in horror, particularly contemporary horror: Hereditary, Suspiria, The Wolf House, and Let the Right One In all offer radically different variations on the same idea. (Some prominent older examples might include The Shining or The Brood.) But I’d be hesitant to place In a Glass Cage’s treatment of the thesis on the same level as these other films. Compared to Hereditary’s evocation of how trauma structures of the nuclear family and domestic space, In a Glass Cage has little to no interest in its nebulously evoked family unit, essentially eschewing it altogether (Griselda is dispatched with as rapidly as possible) for a psychodrama between individuals—and ambiguously sketched individuals at that. Suspiria and The Wolf House frame their narratives within a heady historical context of mass totalitarianism and collective abuses of power. But the background of Nazism in Villaronga’s film feels almost arbitrary. Yes, we see images of concentration camps; yes, we hear of wartime atrocities: but the film isn’t truly concerned with these things in and of themselves; the actual nature of Holocaust violence (insitutional, not individual), its political context, the social setting and history that would be required to make Nazism a subject instead of a mere allusion, all are totally absent from In a Glass Cage’s sequestered mansion. Villaronga shows his hand when he explains that his original inspiration for the film came from the fifteenth century (alleged) serial killer Gilles de Rais, whose crimes he simply transplanted to a more contemporary era by setting them during the Holocaust. His interest is not in Nazism at all. Rather than Klaus’ actions acting as the metaphor for Nazism they’re so commonly taken to be, Villargona reverses the equation: Nazism acts merely as a canvas against which Klaus’ crimes can be contextualized. (The opening credits montage of concentration camp photos is the starkest example of this: the film doesn’t start with Auschwitz because it has anything to say about genocide, but because Auschwitz is as absolute and immediate a symbol of evil as we have in contemporary times—an evil that is immediately linked with transgressive eroticism, as evidenced by the photograph of a male German soldier kissing his gun-toting friend on the cheek.)

Which leaves us with the psychological interpretation, the argument that the film is creating an honest, if not “naturalistic”, portrait of how individuals process the wounds that have been inflicted upon them. The hollowness of this argument, when applied to In a Glass Cage, should be immediately evident to anyone who has seen a film that actually does fit that description, or to anyone who has experienced a comparable trauma themselves. In a Glass Cage is so psychologically flat as to be nearly opaque. Angelo and Klaus do not convince as people or human beings—in truth, they’re little more than shadowy puppets. We don’t enter their psyches and we never really understand their actions, even with the purely nominal explanation their vague histories offer us. If you watch In a Glass Cage as an expression of the “trauma begets trauma” thesis, it becomes an almost risibly simplistic and extremely dull viewing experience, particularly when compared to the richer treatment of this idea in other horror films. In a Glass Cage, frankly speaking, has nothing interesting or intelligent to say about the effects of trauma. And I don’t think it intends to, either. Like Klaus’ Nazism, the trauma explanation serves solely as the narrative pretext for what essentially amounts to an extreme sadomasochistic fantasy: a primal scene of domination and submission so archetypal as to erase any individual histories that might help us understand it.

It is this perceived shallowness of substance that has led some to dismiss it merely as a high-toned exploitation film. And it is. In a Glass Cage is about as pure an example of exploitation cinema as I can think of. It is a film more or less totally lacking in meaningful psychological or political insight, instead drawing its effects almost solely from the lurid magnetism of its perverse scenarios. The handsome cinematographic strategies and trendy historical allusions can’t disguise the whiff of Gothic grindhouse pulp that lurks barely beneath the surface of every single sequence. Villaronga chooses his topics not because his film has something profound to say about them, but because they offer a perfect constellation of absolute taboos with which to attract and repel his audience in equal measure. And his aesthetic strategies certainly don’t subvert the film’s lurid prurience in any way. Instead, they try to provide it with the most thrilling and least mediated means of expression possible.

If I’m coming off as condemnatory, it’s only because I wish to dispute the dominant discourse surrounding this film. The high-minded expectations established by that discourse led to my initial disappointment and frustration with the movie back when I first saw it in 2020. I hope my words have provided a solid counter-argument to this narrative, which doesn’t, in my view, accurately characterize In a Glass Cage’s actual strategies and intentions. Let me now hasten to add that I do still think it is, in its own way, a sophisticated and intelligent work of art. What really makes this movie interesting and worthwhile is that it always remains acutely conscious of its own status as exploitation cinema. Indeed, rather than any narrative theory about fascism or cycles of violence, it is this awareness, which occurs on a primarily formal level, that becomes the very bedrock of the film: the audience’s prurient compulsion to look at, for lack of a better term, “abject” imagery and scenes (a compulsion Villaronga the filmmaker obviously shares) is replicated within the film so many times that it inevitably plays as self-commentary. In a Glass Cage thus ultimately reveals itself to be about the forbidden allure and, yes, the pleasure of looking at and experiencing the unspeakable. “Horror, like sin, can become fascinating,” Angelo reads in Klaus’ diary early on. It might as well be the film’s thesis statement.

I’ve already discussed the carefully staged process of gazing in the opening scene: a precise series of reflexive cinematic gestures (the eye, the lens of the camera, the gaze through the window) that immediately establish both the film’s central theme of forbidden voyeurism—our own as well as the characters’—and align that voyeurism with the cruel perspective of the antagonist. We will remain stuck in this forced point-of-view for the remainder of the runtime: limited to the unsavory options of identifying with either Klaus or Angelo, the audience always shares a sadistic perspective that derives sexual gratification from violence and domination. This disconcerting strategy, which weaponizes the horror moviegoer’s morbid appetite for disturbing scenes and acts against itself, finds echoes in Haneke’s Funny Games and, more obviously, Pasolini’s Salò, to which In a Glass Cage is often compared. But the comparison is immediately short-circuited by the stylistic qualities of each film. In a Glass Cage has nothing of Pasolini’s formal austerity and icy restraint, the qualities which constitute the crux of Salò’s aesthetic and moral project. The constantly shifting sense of distance in Pasolini’s film ensures that our own prurient fascination with these awful scenes remains constantly foregrounded and self-indicting. Villaronga similarly emphasizes that fascination, but instead of indicting it, he actively indulges in it.

His camera avoids the merciless wide shots of the austere approach to violence, instead electing to squeeze the mise-en-scène for every richly Gothic effect it can elicit. We’re treated to sweeping camera movement, startling and dramatic editing, and intensely stylized lighting, abandoning itself to every gloomy shade of blue, nightmarish architectural detail, or thick pool of shadow it can find. The atmosphere is lush and evocative, absorbing and suspenseful; even when it’s frightening or disturbing (and it often can be), it’s never truly disgusting or depressing in the way a film like Salò is. Just take a look at Griselda’s death sequence, an extended tour-de-force of grippingly emotive, suspenseful filmmaking that has rightly earned the film comparisons to the best of the giallo genre, and you’ll see quite clearly that the true divinity behind this film’s seductive chill is Argento, not Pasolini.

Outside of the opening, the scene that most successfully communicates In a Glass Cage’s confluence of ideas, style, and purpose for me is a murder that occurs near the climax: Angelo’s slaughter of a boy soprano he’s abducted from a nearby school. Villaronga pulls out all the stops for this scene, investing the already transgressive subject of child murder with a deeply disquieting eroticism and leveraging his toolbox of cinematic effects (a dense, tensely edited collage of camera movement, costuming, sound design, color, shadow, flame, smoke, etc.) for maximum effect. Here the narrative fixation on sexuality and death and the formal fixation on complicitous voyeurism and fantasy reach their fullest expression.

Klaus, as always, is trapped in his iron lung during this scene. Angelo has manipulated the little mirror above Klaus’ eyes to control his line of vision: he is forced to witness the murder, unable to look away. This compromised position, which incidentally anticipates a similar device in Argento’s Opera just one year later, has often been analogized in the academic literature on the film to the position of the cinema spectator in relation to Villaronga’s images. That affinity is the most important element in the film’s reflexive arsenal, particularly as we’re pushed into an instinctive sympathy with Klaus’ suffering—it mirrors our own suffering as victims of the film, of course. But just as Klaus has brought this suffering upon himself through his past actions, the audience has implicitly consented to this sight by virtue of their very presence in the theater: a presence essentially determined by, whatever the individual justification may be, a fascination with the taboo subjects In a Glass Cage has on offer, a willing subjection to whatever horrors it may serve up. This sadomasochistic contract between director and audience finds its mise-en-abyme in Klaus’ half-agonized, half-engrossed stare into the targeted mirror, the crucial element of self-consciousness that pushes the film just beyond the basest form of exploitation.

Intercut with shots of Klaus’ gazing (much like the beginning of the film), we witness the murder itself through the subjective viewpoint of a sadist. Villaronga draws out the terrified boy’s gradual stripping in a long take before coming in close for the kill, following Angelo’s leather-gloved hand as it slides down the boy’s bare, shivering chest in a frankly sensual caress. This is a genuinely shocking, even amoral presentation of such a subject, one that encourages us to join in its fantasy of abject eroticism. One cannot escape the feeling that one is looking at something forbidden—which, the film is well aware, is exactly what gives the sequence its disturbing excitement, and a consciousness that it subtly but firmly neuters through its blatant artificiality. The sequence climaxes in a flagrantly dramatic, aestheticized fantasy of violence: Angelo’s glinting knife slitting the boy’s throat, unleashing an orgasmic gush of dark red blood that surges down his torso before dissolving into crackles of flame. The exquisitely fetishistic imagery of this scene should completely settle that this is not a film about history or society or trauma, but rather the erotic thrill of evil: a thrill Villaronga invites us to share in, himself shares in, in the awareness that it is entirely artificial.

All of these cinematic strategies aim to play upon the perennial fascination with the ambiance of death, sex, and evil. We’re kept conscious of that fascination through a series of self-reflexive devices, but we’re never distanced from it or judged for it—we’re not even asked to analyze it. On the contrary, Villargona’s seductive style encourages us to break from the silence ordinarily surrounding such subjects and to freely lose oneself in the amoral pleasures and pains of simply looking at them. The dominant impression is one of fantasy and play, of an intense (but never persuasively “real”, and thus never truly threatening) exploration of the social imagination’s outer limits, and as such In a Glass Cage begins to act almost as a self-aware reflection on the function of horror cinema itself—a certain strain of horror cinema, anyway. Seldom will you find an exploitation film so refreshingly honest about its intentions: it’s not acting as political or psychological commentary, but as a fictive window into the scenes of our culture’s deepest fears and fantasies. A collocation of taboos—fascism, sexual violence, torture, homosexuality, and sadomasochism—are all presented as if off a checklist, but it is Villaronga’s technical skill in stoking our morbid curiosity about such subjects, along with his frequent self-conscious gestures at the audience and at himself, that make this a much smarter and more memorable exploitation film than most. Its clever selection of especially lurid material comes into full focus when viewed in the political context of its day: la Movida Madrileña, that great outpouring of creative, countercultural, and transgressive artistic energies in 1980s Spain during the transition out of dictatorship to democracy, a period that In a Glass Cage was released almost at the direct midpoint of. Almodóvar was giddily conjuring the same taboos in his comedies and melodramas of the period; Villaronga does the same in a horror film. In both cases, it is not the topics themselves that interest the directors or the audiences, but rather the ecstatic creative freedom of expressing all that has remained inexpressible and unmentionable: the amoral delight of pure social transgression.

The glass cage of the film’s title, while literally referring to Klaus’ iron lung, has often been taken to symbolize the way trauma affects these characters’ lives, imprisoning them in invisible traps, limiting their movement to familiar pathways of violence and subjugation. But having watched the movie twice now, I’m more inclined to think that Villaronga shows us his eponymous subject right in the second shot. The glass cage is that of the camera lens, of the cinema screen itself: a translucent scrim through which we can view our most perverse and unutterable fascinations, safely distanced from them by the artifice of fiction and irreality. Is that boundary secure? The answer is already obvious in how quick the film’s characters are to reenact the violence they both witness and endure, the sway their dark passions exert over their lives—and, by extension, our own. Glass is easily broken, after all.