During the 1970's, J.G. Ballard was creating an absolutely amazing body of work, some of the most important fiction being written in the 20th century. Cold surgical tales that mercifully examine our times and our place in these strange new times. A pornography of science fiction. A science fiction of pornography. Like Ballard says, pornography exposes our desperate need to use and exploit each other. And in the vast media dreamscape that has overtaken all of us, we are free to explore our most secret perversions and act on our most deep-seated hatreds. Ballard endeavors to look head-on at what over lit future we were about to find ourselves in.

Coming from a tradition of science fiction that was becoming increasingly safe and stale, Ballard took the field in a completely new direction. Science fiction was stagnant, still exploring space fantasies first innovated by Wells, Verne, and company, it had become a purely escapist literary genre. Ballard, in his focus on what he called inner space, on our society, and on the body and identity, changed the trajectory of the field. Ballard brought a new transgressive motive to the field, making work that was challenging, sometimes pornographic, sometimes abstract, and refused to fall into the science fiction tropes that only served to reassure the goodness of man and of humanity's great future destiny. Ballard saw the future as being cold and perverse. An erosion of emotion and an increase in the freedom to explore your own psychopathology. His work during the 1970's was transgressive and experimental, explorations of the future that was coming, or the future that we were secretly wishing for.

The Atrocity Exhibition (1972) is a collection of semi-related stories that examine the breakdown and ruin of both our culture and inner lives. Our dreams and our identities are corrupted and perverted by the victorious media landscape and the absolute takeover of technology that has enveloped all our lives. We can not escape the complete corruption of our lives by technology and media. The labyrinth is so deep and complex that we can no longer distinguish between what is reality and what is fantasy. And The Atrocity Exhibition is a surgical examination of our fractured lives and psyches.

Crash (1973) shows us an apocalypse. Not one that is going to happen. Not one that has happened. But one that is ongoing every single day. An apocalypse we willingly engage in, enter into. Thousands die on the highways every year, a veritable mechanized genocide. In our media, we are bombarded with images of car crashes and car violence, and we are always demanding more. What may be the first truly pornographic science fiction novel. A true classic, shocking and alluring at the same time.

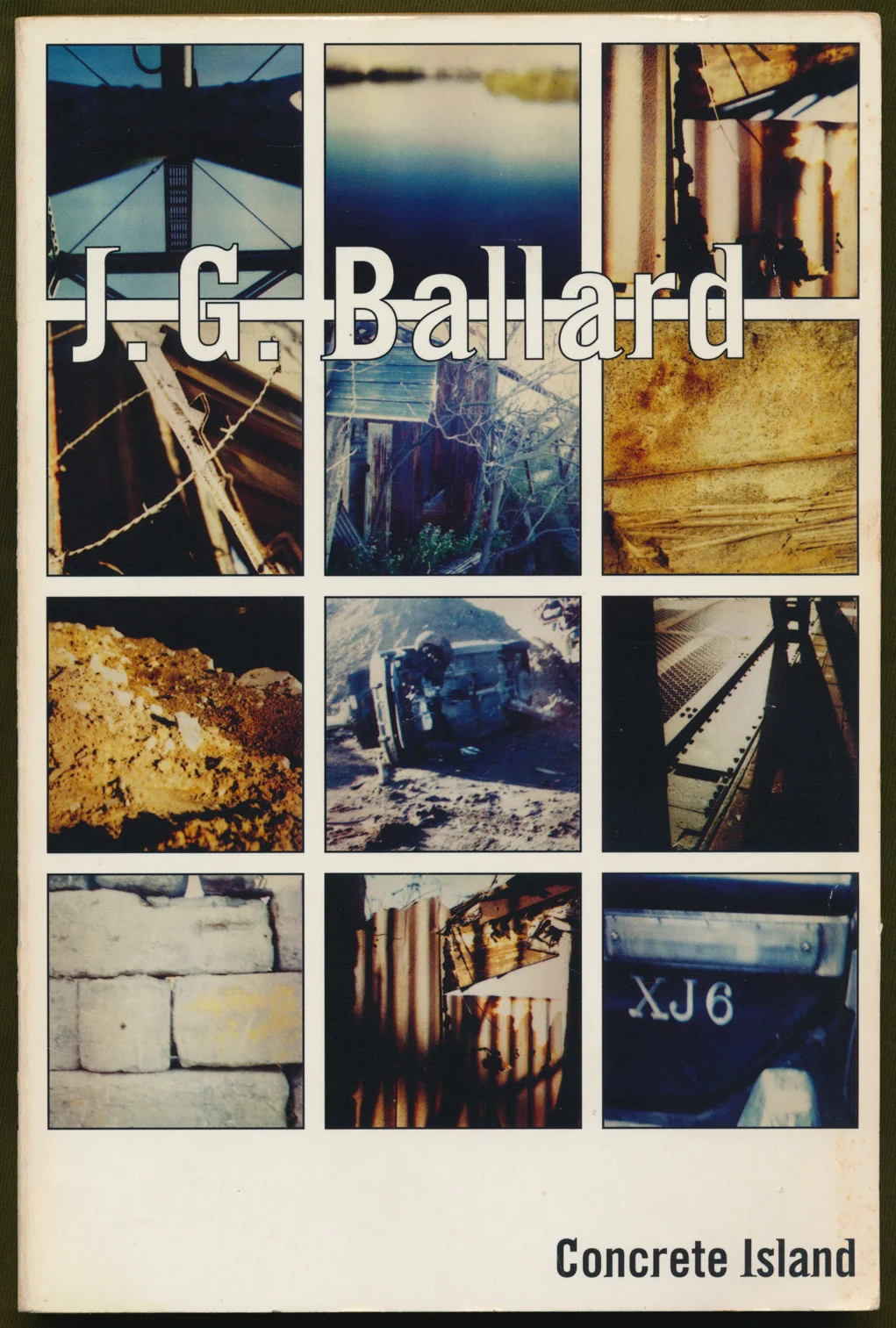

Concrete Island (1974) is a subtle tale of alienation. An abstract tale told as a stranded island tale. The main character, finding himself stranded in the middle of a maze of highways, literally trapped on a concrete island, the novel explores his secret desires that have been largely unknown to himself. Maybe the most understated work of this period. The concrete island of the title becomes the inner mind of the protagonist.

High-Rise (1975) is a sometimes interesting book, but Ballard’s provocative vision and innovative views on modern society aren’t as sharp in this one. He often times here falls back on overused symbolism, and his ideas are a bit too obvious and overstated. Class warfare literally played out over the different floors of the high-rise apartment building. A modern apartment building with all the amenities to make all its inhabitants feel comfortable and safe. Safety lulls the modern apartment dweller into wanting to break from the comforts of modern life and seek perversion and violence. Ballard is trying to write a kind of 120 Days of Sodom, full of perversion and classism, but sometimes it tends to come off as just cliché. It is a worthy book, but maybe the least of his works from this era.

The Unlimited Dream Company (1979) is Ballard stepping away from the cold, sterile science fiction of his “concrete era” and into the world of dreams. This is Ballard fully embracing his interests in surrealism. Characters who may be alive or may be dead. The most inner desires and dreams made real. Ballard’s dark edges and perverse sexuality are still in full display here. But this is a more passionate book, full of dreams and fantasy. It comes from the same imaginative core as the “concrete era” books, just a change in texture, in expression. It signals a move for Ballard to move away from being cold and clinical and into a more active interest in exploring human relationships and emotional states in his future novels.