Why do we enjoy horror stories? There have been a million attempted answers to the question, and almost none of them are satisfying—or entirely satisfying, at any rate. A common view holds that exposing ourselves to our deepest fears in a safe and artificial environment helps us prepare ourselves for and cope with them when they arrive in the real world, but this seems to fall apart with even the merest scrutiny: watching Antichrist would not seem to ease the pain of losing a child, for example, nor am I likely to recommend Audition to someone with a fear of needles. Stephen King, who once proposed this view in his 1981 survey of the genre Danse Macabre, has alternately contended that watching horror movies allows us to satiate our deepest, darkest instincts and thus to keep them at bay, but again, this suggestion fails to account for so much; when I walk out of an especially traumatic or upsetting picture, I don’t feel that anything has been “purged” from me, I feel worse. Ligotti perhaps strikes closer to the mark when he argues that horror is the best genre for reflecting the eternal agony and absurdity of the mortal human consciousness, but I don’t think we can assume this holds true for a huge portion of the audience for horror movies, either. In each case the proposed answer seems either too trite, beholden to fundamentally conservative notions of art as serving some redemptive social or psychological function, or too specific, expressing a highly individual philosophy of life and existence that doesn’t adequately account for the genre’s popular appeal.

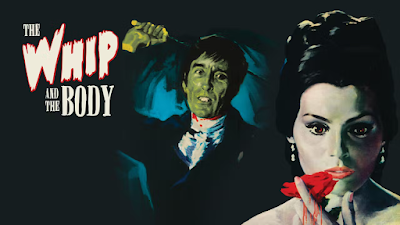

Without hazarding a guess of my own, I’d like to examine another response to this perennial question, a response suggested by the great horror auteur Mario Bava in his 1963 Gothic chiller The Whip and the Body. Unlike the above proposed explanations, The Whip and the Body almost radically centers a very simple and uncomplicated experience at the locus of the horror genre: that of pleasure. A strange kind of pleasure, to be sure, that derives itself from immersion in negative emotions, from scenes of death and degradation, from abject misery and anguish—but pleasure all the same. In short, the pleasures of masochism, that curious disposition that finds gratification and fulfillment in the darkest of places.

Masochism is, indeed, what this suggestively titled picture has been most remembered for, owing to the numerous cuts demanded upon its release by various censorship boards in multiple nations. Its unsubtle allusions to “degenerations and anomalies of sexual life,” as a Roman court declared in 1963, occasioned the butchering of the 91-minute film into a nearly incomprehensible 77-minute international cut, released in the United States with the fittingly perplexing new title of What!. The furor was mostly due to an early scene in which the female protagonist Nevenka (Daliah Lavi) submits to an erotically charged lashing from her former paramour, the imperious Kurt Menliff (Christopher Lee). This brief sequence, in combination with its winking title, accounts for The Whip and the Body’s reputation as a playfully kinky, if otherwise fairly standard and by-the-numbers, Italian Gothic of the early sixties. It’s not received nearly as much discussion as the consensus-held masterpieces of Bava’s oeuvre (Black Sunday, Blood and Black Lace, Bay of Blood, and Black Sabbath among them), and when it does, the sexual current of the film is spoken of mostly as if it were a gimmick, teased at in a few superficially titillating scenes but overall subordinate to the director’s stylishly gloomy atmospherics.

It’s true that the slight scenes of masochism in The Whip and the Body are quite tame by today’s standards, hitting nowhere near the level of explicitness or perversity that would come to be regular fare in exploitation films only a few years later. Indeed, following that initial whipping scene, Nevenka’s sexual proclivities are hardly ever addressed—or at least directly represented—again, outside of a few scant moments and mentions. It’s presumably this reticence, or even potential disinterest, in probing the extremes of its implications that has led many critics to ignore or significantly downplay the sexual tensions of the film, instead preferring to situate it within Bava’s overall oeuvre by addressing its familiar motifs. But to do so is to fail to recognize that masochism is integral to the very texture of the film: that in truth it is the film’s principle subject, in ways far more fundamental and interesting than the mere surface play of its meager erotic scenes.

The narrative of The Whip and the Body is very simple. Kurt, the eldest son of the Count Menliff (Gustavo de Nardo), has been exiled for his entanglement with the servant girl Tania, a dismal affair that ended in the girl’s suicide. Kurt had been engaged to the beautiful Nevenka; in his absence, she marries his younger brother Christian (Tony Kendall) instead. One dark night Kurt returns, distressing the entire family, most especially the mother of the servant girl (Harriet Medin), who longs for Kurt’s death. He coldly offers his congratulations to Nevenka and Christian, but he obviously wishes to reassert his place in both the nobility and Nevenka’s heart. On a dusky beach, he reignites their sadomasochistic entanglement, flogging her with a riding crop, reigniting in her a confused disorder of passions she had hoped to leave behind. But that very night, in a highly oblique and mysterious series of events, Kurt is murdered by an unknown culprit. Quite shortly after his death, his ghost begins to stalk the castle, leading Christian to investigate the mysterious circumstances of his murder and ultimately culminating in tragedy for Nevenka.

On the surface, this reads like a stock Gothic plot, with only the barest hint of sexual sleaze to differentiate it from any other number of lurid Italian productions of the day. And it’s true that the plot is probably the very least interesting thing about The Whip and the Body, the element that feels the most underdeveloped and unrealized. At times, when it focuses on Christian’s quest to determine the murderer, it can even feel downright laborious, merely a series of ponderously paced generic machinations to provide a flimsy canvas for Bava’s lush aestheticism. It’s hard to fault those who take issue with the somnambulant slowness of such predictable and well-worn genre clichés. The beauty and subtlety of the visual craft do not extend to the details of the screenplay.

But the film nonetheless finds an emotional and thematic key in the personage of Daliah Lavi. Her performance as Nevenka is so completely absorbing that she even manages to upstage the great Christopher Lee, who by comparison comes off as stodgy and wooden. (In all fairness, the horrendous dubbing endemic to Italian films of the period can’t be helping.) In a production full of cardboard cut-out horror movie stereotypes, the psychological intensity and uneasy ambiguity of Lavi’s role emerges with startling force. It is in her that the film locates its dark core.

For even though it is only overtly addressed in the early scene on the beach, the performance makes it clear that Nevenka’s masochism permeates every aspect of her being. Her reaction to the haunting has a troubling ambivalence unfamiliar to the Gothic heroine of more conventional stories. Lavi intentionally acts in a manner that blurs the distinction between gasps of fright and moans of pleasure; when she shivers, it’s uncertain whether it’s out of fear or exhilaration. Terrified glances become indistinguishable from desirous ones. This is The Whip and the Body’s real surprise: not the shallow tease of skin, but the sense that the horror is not inimical to, and perhaps even willed by, the person who we assumed was its victim.

Consider the film’s most frightening scene, a nocturnal visitation from Menliff’s ghost to Lavi’s bedchamber. After an extended period of excruciating build-up, during which the doorknob gradually turns at the touch of an unseen hand and Menliff’s silhouette (bearing the same riding crop) looms before the window, we are jolted by the terrifying image of his hand slowly extending toward her—toward us—out of the darkness. She screams, but instead of running away, she rolls onto her back, an identical posture to that attitude of eager submission in the beach scene. The hand caresses her cruelly, commandingly, before tearing her nightgown open. These are the gestures of sadomasochistic theater as much as they are thrills in a horror set-piece. The fact that this sequence acts as a double of the earlier erotic encounter on the beach points to the dissolution of boundaries between death and desire, pain and pleasure, horror and fascination that the film will affect even further in subsequent scenes.

The truth is that Nevenka does seem to feel fear at all in response to Kurt’s return from the grave—or more accurately that her fear is indissoluble from, indeed synonymous with, her happiness. For her, the haunting is not a curse or a nightmare, but a state of sexual fulfillment; the horror movie villain is not an antagonist, but the enforcer of her repressed desires. Over time, we come to see Kurt as servicing Nevenka rather than terrorizing her. Certainly, he seems to at least understand her more than the supposedly virtuous Christian, who Nevenka witnesses engaging in an adulterous rendezvous with another woman. Heartbroken by his hypocrisy as much as his betrayal, she flees to a private room, where Menliff’s specter appears next to her in a mirror. She cowers and falls on the bed, where he whips her once more, more brutal than ever; but despite her theatrical protestations, she is quite discernibly and unequivocally moaning in sexual ecstasy, even smiling. “I’ve come for you,” Menliff tells her, in another telling double entendre. Quite contrary to the menacing threat we might typically interpret in such a statement, the implication is almost poignantly romantic. He has come for her, for her benefit, to serve her, because he knows this will make her happy, happier than she could ever be with the dull and proper Christian. For her dread and pain are inseparable from joy and eroticism: Kurt’s aggressive resurrection, by which he can exert total terror and dominance over her, thus presents the most complete realization of the masochistic scenario possible. And it is my contention that this masochism implicitly doubles and illuminates the pleasure we as audiences often take in horror as a genre: we are drawn to these macabre scenes and ghastly experiences for themselves, not in spite of their negative emotions but because of them, because we find in them a pure and indefinable gratification loosely analogous to the sexual titillation the masochist takes in pain.

For clarity’s sake, it might be worth briefly contrasting this with a diametrically opposed but curiously complementary philosophy explored in another film: Michael Haneke’s infamous home invasion experiment Funny Games (1997). The young torturers in Funny Games have also come “for us”, the audience: the horrific violence they enact upon an unsuspecting bourgeois family is for our entertainment as viewers, an awareness rendered chillingly clear through a number of Brechtian fourth wall breaks. In this way, Haneke aims to expose, explore, and critique what he understands as the audience’s sadistic voyeurism, evidently the underlying fantasy not only of many a horror film but of numerous forms of media consumption relating to images of violence. But what we find in The Whip and the Body seems to suggest that this claim is limited, at least when it comes to the horror genre. Bava instead proposes a masochistic understanding of spectatorship, predicated on identification with the victim rather than with the killer. We come not to terrorize, but to be terrorized; our pleasure is not derived from the thought of inflicting violence on others, but from experiencing the fear and agony of being subjected to violence at a physical remove. We do not align ourselves with the hollow coldness of the sadistic Menliff, who doesn’t even have enough personality to securely latch onto, but with Nevenka’s dark and heated passions, her inexplicable lust for pain. The terror she experiences is a crucial part of the thrill, the central and consensual term both of her unspoken contract with Menliff and our contract as viewers with a filmmaker: she wants this, and so do we.

Viewed through this lens, the whole of Bava’s filmic style takes on an almost subversive new meaning. The creaky trappings of old dark house pictures are reframed as the fetishistic signifiers of a totalized perverse fantasy: the fluttering curtains that bind and strangle Menliff before his death; the sinuous hanging branches that grope and choke the shadowy mise-en-scène of the ancestral vault; the darkened passageways, sliced by slats of icy light, that come to resemble the internal passageways of the human body. The more her madness progresses, the more Nevenka herself seems to merge with this environment, which comes to feel closer to a fearsome emanation of her ghastly desires than anything else. When Christian discovers her swooning in Menliff’s crypt late in the film, the panting sighs she emits as she languishes on the stone floor are more suggestive of necrophiliac euphoria than the shock of a kidnapping victim. The men are baffled, try to impose explanations, but she remains steadfast in her solitary quest. And Bava recognizes that, at least in art, this obscene pursuit has an inevitably suicidal terminus. The ending, which goes so far as to suggest that the ghost may have been a hallucinatory manifestation of Nevenka’s desires the entire time—not that the difference ultimately matters—finds her plunging a dagger into her breast to Christian’s great horror. But this penetration is also a consummation, and she expires with the stamp of contentment on her face. “Let’s hope she’s free of him forever,” Christian mournfully remarks, but the final shot of hellish flames blazing over the smoldering remains of the riding crop suggests that her violent delights may not be extinguished even in death.

An exemplary early sequence, just as the haunting is beginning, shows Nevenka wandering the midnight corridors of the castle, drawn by an unusual sound to a heavy wooden door at the end of the hall. Bava intercuts between shots of the door and ever-intensifying close-ups of Lavi’s face as she approaches. Light and shadow play so delicately across her features that we’re unable to clearly identify her expression. We hear her quick, short pants of agitation, but it is impossible to tell if her mouth is curling in a grimace or a smile, if her widened eyes suggest building anxiety or yearning anticipation. By the time she is turning the handle the tension has reached an almost unbearable pitch, but, as any horror fan knows, the sickening frisson of suspense is also a source of ardent excitement. What lies beyond that door? Her worst nightmare? Or her darkest desire? The singular pleasure of The Whip and the Body is to suggest that there is no difference.