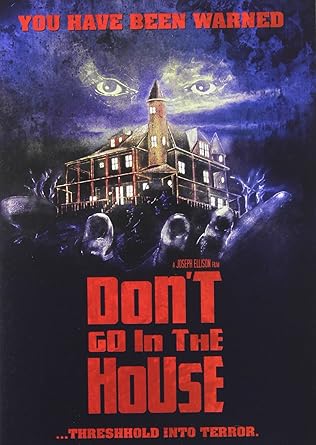

While most people would suggest THE SHINING or THE THING as the most effectively chilly winter-set horror films, I would instead offer 1980's DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE, not only because its authentically dead-of-winter Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey settings more chillingly capture the desolation of the season, but because it's an icy film down to its core, a portrait of isolation and loneliness where human warmth is as impossible to imagine as any kind of sunny seasonal relief.

Even though DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE was marketed as just another late '70s/early '80s slasher film, there is no vicarious thrill involved in the gory effects, which are largely limited to an absolutely horrific burning sequence that is bound to be seared in your memory forever. However, the film - which was co-written by husband and wife team Joseph Ellison (also the film's director) and Ellen Hammill (a producer of the project) - is more of a character study of a TAXI DRIVER-like loner named Donald "Donny" Kohler (played by the brilliant Dan Grimaldi). This makes DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE one in a series of ultra-downbeat NYC-area horror films of the period such as 1979's DRILLER KILLER (Abel Ferrara), 1980's MANIAC (William Lustig), and 1982's THE NEW YORK RIPPER (Lucio Fulci) that are studies of urban alienation.

Throughout his childhood (and more than likely, adulthood, as well) Donny was physically abused by his mother. In the recently discovered director's cut of the film (released on Blu-ray in 2016 by Scorpion), there is a scene in which Donny goes into great detail about the abuse he suffered at the hands of his mother, as well as how her domineering actions lead to the departure of his father. This trauma made him unable to relate to the rest of society, and as a result, Donny begins hearing voices after his mother's sudden death and is driven to brutally murder a number of female victims by burning them to death. As with films like 1978's MARTIN (George Romero), 1979's DRILLER KILLER (Abel Ferrara), and 1986's HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER (John McNaughton), empathy for the murderous protagonists' plight (and in some cases, their histories of abuse) does not encourage identification with their violent ways of "coping" with their traumas, and the films - contrary to assertion by feminist critics of slasher films of the era - don't encourage viewer identification with their murderous and sometimes misogynistic actions.

During the span of the film, the audience experiences Donny's extremely brief encounters with his victims, but we are never truly familiarized with most of the film's supporting characters. The only exception is a character named Bobby Tuttle, played by Robert Carnegie (who has been Dan Grimaldi's best friend since working together on the movie). Bobby is a co-worker of Donny's and the only person who truly cares about his well being. While their other co-workers at the incinerator regard Donny as a bonafide weirdo, Bobby accepts the role as his protector (he even covers for Donny when their boss questions his absences). It becomes obvious that Bobby is the only person with whom Donny could form a genuine connection. Unfortunately, our protagonist lacks the tools to form a real friendship or to function in society. In one of the film's most famous scenes, Bobby witnesses Donny completely unravel at a popular discotheque when Donny catches his date's hair on fire. To no avail, poor, oblivious Bobby spends the rest of the film trying to help his friend.

There are a few unforgettable key elements that contribute to the cold, alienating feel of the film. One of the most important is composer Richard Einhorn's minimalist synth score that adds suspense while Donny's psychosis begins (and continues) to take hold (DON'T GO INTO THE HOUSE was the second film he scored, and he has since become a composer that is in high demand). Another of these elements is the film's use of a sparse aesthetic that frames its characters in almost total isolation. The eerie location shooting makes it similar to other classic horror films like 1973's MESSIAH OF EVIL (William Hyuck) and DON'T LOOK IN THE BASEMENT (S.F. Brownrigg).

Interestingly, despite the obvious similarities with William Lustig's MANIAC (a harrowingly claustrophobic portrait of a misogynist serial killer operating in the dead of winter in the NYC area), DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE also has a surprisingly identical climax, with the mutilated corpses of both men's crimes coming back from the dead to wreak their deserved vengeance. Given that MANIAC is the more popular film, one might be inclined to think that Ellison and Hammill appropriated their denouement from the Lustig splatter landmark...if it wasn't for the fact that DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE was actually released almost a year earlier (shot in 1979, HOUSE hit theaters in March of 1980, whereas the Lustig film didn't hit grindhouses until January of 1981). And the approaches adopted by the films also differ strongly: HOUSE and MANIAC are two of the late-70s/early-80s' strongest, most brutal and unsparing horror film portraits of unraveling urban psychosis, and as far removed from the reassuringly "safe" territory of monsters and the supernatural as imaginable. Yet while MANIAC suggests that the uprising of cadavers that tear apart Joe Spinell's murderer are indeed a hallucinatory figment of his damaged psyche -- a coda reveals police finding his body intact, an apparent victim of suicide -- HOUSE leaves the actual nature of Donny's climactic demise more ambiguous. There is no epilogue to suggest that the undead uprising is all in Donny's mind -- and, more tellingly, there is a brief shot just prior to the attack that even privileges the viewer by allowing them to view a reanimated cadaver lurking in the background, that -- notably -- is entirely unseen by Donny. For a "slasher" film of the era that represents one of the most grimly realistic of the genre, it's a fascinating choice to close on an enigmatic note that leaves the viewer as uncertain about reality as Donny himself.

DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE is not a "fun" horror film filled with outrageous gore FX and campy humor, suitable for viewing in a social atmosphere with friends and malt liquor options. Like Donny and the environment in which it's set, the film is bitterly cold and uncomfortable viewing. But for those horror fans who like their evening's entertainment to be pitch black and grim, it's a haunting and unforgettable gem.

No comments:

Post a Comment