Welcome to the Plutonian! Your yearly anthology series Nightscript has been a favorite of mine since issue one. For my money, it may be the best yearly weird horror anthology around. What was the genesis behind you creating Nightscript?

It’s an honor to be here, and I am heartened by your kind words. Thank you. As to the genesis of the anthology, there are, oddly enough, two points-of-origin. Back in the late ’80s, during my junior year of high school, I produced a staple-bound horror anthology called (yes, you guessed it) Nightscript—as a young kid, I was extremely proud to have fashioned this catchy compound word. The first issue contained half a dozen stories and was produced at the print shop where I worked. This was my last job before venturing off to college where my love of horror fiction and the anthology I had once been so proud of quickly washed down the academic drain. Flash forward to 2012, or thereabouts, and I found myself returning to horror fiction, though more so on the writing side of things. I worked hard for a couple of years, trying to improve my style and occasionally submitting pieces to prospective markets. There was zero success, but with a bit of persistence and luck I finally found a home for a short piece entitled “Vrangr.” And what a home it turned out to be: Michael Kelly’s Shadows & Tall Trees. I mention this because I don’t believe Nightscript would have been reincarnated had not this seminal event in my writerly life occurred—for when the unfortunate news hit (about a year after my story acceptance) that S&TT would be entering a state of indefinite hiatus, I was saddened to imagine the possibility that such a unique and seminal publication might never again see the light of day. So, all of my old experience from that long-ago print shop anthology returned and I thought why not give it a go. I was confident I had the technical expertise, though remained skeptical about the publication’s reception, i.e. how to market it. But sometimes, as we all know, we just have to trust our intuition. To paraphrase the immortal words of Ray Bradbury: I threw myself, idea in hand, over the cliff and built my wings on the way down. And what a ride it has been!

Nightscript has this nice blend of different genres, like weird horror, dark fantasy, and ghostly fiction. What is the “mission” of Nightscript? What kind of impact do you wish it to have? What kind of work are you trying to champion?

I originally envisioned a much smaller publication that would have included no more than a dozen stories, all in the mode of Robert Aickman. My intent, from the outset, was to focus exclusively on “quiet horror.” After putting the call out for stories, however, my perspective on the enterprise shifted considerably. I realized that limiting the type and quantity of fiction I was looking to include was not really the route I wanted to take. I’m not afraid to admit that for the entirety of the year that the first volume was in production, I was anxious to the Nth degree. While I knew there was enthusiasm in the community, I had no idea that the project would eventually be so well-received. Indeed, no less than Ellen Datlow called it “a very promising debut anthology” in her Best Horror of the Year. Readers also seemed to like the aesthetics I was going for, and so I felt encouraged to expand the project outward. Hard to believe that I will soon be reading for Volume 5! I think my main goal of the anthology has always been to promote exceptional writing and stories that resonate. And just what is “exceptional” writing? Well, for Nightscript I would say that a potential entry needs first and foremost to be dreamlike, in the sense that the writing (the content and the style) must lull me into an experience that is both emotional and new. Sure, there is always the entertainment side of the reading experience, but there needs to be something more. Des Lewis, in his Real-Time Reviews, summed the anthology up best: “Weirdness with truth at its heart.”

Your Chthonic Matter Press was a huge influence on me to start my own little micro publishing press, Plutonian Press, and publish my own anthology, Phantasm/Chimera. What are your thoughts on the micro/small press publishing world?

You know, that is so fantastic to hear. It really is. One of my goals/hopes at the outset was to encourage/inspire others to step into the role of editor/anthologist. For me, there is no better feeling than knowing that I’ve in some way inspired others to create. While there are many benefits to be had in regard to publishing an anthology, I would say that this, as well as the discovery of new talent, are the most rewarding. My thoughts on the micro/small press scene are simple to summarize: This is where it’s at, people. This is where some of the best writing can be found. Sturgeon’s Law, right? Ninety percent of everything is crap. Well, I’d say that the majority of that exceptional ten percent can be found in the micro/small press sphere. I guess it all boils down to what excites and inspires you. For me, a lot of the work being published in this “underground network” is the stuff that will be around for some time to come. Perhaps this is because we have for the most part distanced ourselves from the big business publishing model, where sales are more important than substance. There’s an energy and originality that exists here that I simply do not find in the upper echelons of the publishing biz. There are exceptions, of course, but overall I would say that I am inspired almost exclusively by the “Davids” in this Goliath story.

You also are a masterful writer of quiet horror fiction. What is the seduction of the creepy and the unnerving to you?

I’d ask that you redact “masterful” and replace it with “middling,” but I sure do appreciate such a kind classification! You know, I wish I could give you a more proper explanation about the “seduction” that this type of fiction affords, but it really is a difficult question to answer. I guess we all consume stories for different reasons and in different ways, whether we are a Writer, Reader, Anthologist, or a combination of all three. We draw forth technical things, emotional things, things which enlighten us, things which explicate the joys and horrors and mysteries of the human condition. Ah, the hell with it—let’s just keep the Mystery of it all intact and enjoy it while it lasts.

If you were to publish an anthology of your all-time favorite horror short stories, what are some of the stories you would choose?

Well, I could certainly fill dozens of volumes, but I will limit myself to ten:

Lisa Tuttle’s “Bug House”

Jason A. Wyckoff’s “Knott’s Letter”

Shirley Jackson’s “The Summer People”

Terry Lamsley’s “Walking the Dog”

Jerome Bixby’s “It’s a Good Life”

Mike Conner’s “Stillborn”

Clive Barker’s “Coming to Grief”

Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People”

David J. Schow’s “Not From Around Here”

Brian Evenson’s “Windeye”

With Halloween just around the corner, I would be remiss to not ask you, what are you favorite go to horror films to watch in October?

The one which readily comes to mind (largely because I just acquired a VHS copy at Goodwill last week) is Halloween 3: Season of the Witch. This is always a fun one to immerse yourself in. (And, bonus, the storyline does not include that creep, Michael Myers!) I’m also curious about the new Haunting of Hill House remake currently playing on Netflix. Another film I might mention is Philip Ridley’s The Reflecting Skin. If there is a Nightscript story which could be said to have been translated to the silver screen, this might very well be it. Such a brilliant movie, on so many levels. One of my absolute favorites.

You have a new anthology coming out in 2019, Twice Told: A Collection of Doubles. I do believe that the book is themed around Doppelgangers? What drew you to this theme? And are we going to be seeing more stand-alone anthologies from Chthonic Matter Press?

Yes, I am extremely excited about this project. The contents (22 stories) are absolutely incredible, and I think readers will be pleased with the unique approaches each writer has taken in regards to the theme. As far as what drew me to such subject matter: Hey, what’s not to like about coming face-to-face with a duplicate of yourself? There’s something unnerving and delightful about the idea. What I was hoping to achieve with this stand-alone anthology, however, was to avoid, as much as possible, the traditional route of the doppelgänger, and for the most part, I think I have succeeded. I will be curious to see how it is received. And, yes, I have a number of ideas for similar stand-alone anthologies in the coming years. I can’t speak of anything definitive as yet, but if things go well with Twice-Told, I’d say that there is a strong likelihood that other themed anthologies will be born. I’ve also been tinkering with the idea of starting another non-themed anthology, a sort of sister publication to Nightscript, though something a bit more SF-oriented, à la Black Mirror. Given the current environment in which we live, this seems like a pertinent and exciting avenue to explore. I feel that there might be a good bit of crossover from the weird fiction community, and so perhaps the time is right to take yet another plunge from Bradbury Heights.

What can we expect next from C.M. Muller and Chthonic Matter Press?

First off, I’d like to thank you for providing this platform, and for your unflagging encouragement these past few years. I have four stories that should see print relatively soon. They are slated to appear in Vasterian, Weirdbook, Gorgon: Stories of Emergence, and the Stefan Grabinski-inspired anthology In Stefan’s House edited by Jordan Krall. I’m super excited to be included in these publications. I’m also planning to release my debut story collection later this year, entitled Hidden Folk, which will contain twelve or so previously published tales. And, last but not least, there is the continuing dark saga that is Nightscript: I’ll be open to submissions for Volume 5 this January. I have a feeling that 2019 is going to be an insanely busy but incredibly inspiring year. Onward!

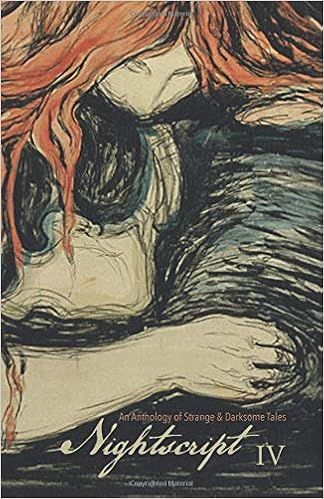

Buy Nightscript 4 here:

https://chthonicmatter.wordpress.com/nightscript/

Buy Nightscript 4 here:

https://chthonicmatter.wordpress.com/nightscript/