I am super excited today to have Jon Padgett stop by to talk about some of his projects that are dropping in 2018. He has a spoken word adaptation of Thomas Ligotti’s seminal short story The Bungalow House coming out from Cadabra Records in May. The Bungalow House will be released in a vinyl edition and is available for preorder at the Cadabra Records website. And he also has, what I think may be the most exciting book being released this year, Vastarien: A Literary Journal, coming out with his co-editor Matt Cardin. In 2016 Jon released his modern classic of weird horror, The Secret of Ventriloquism. And you can also find his short story, The Great, Gray Bulk, in my anthology from 2017, Phantasm/Chimera. Welcome back to The Plutonian Jon!

Thanks, Scott! Such a pleasure to speak with you again.

First off, I would like to say congratulations on all the exciting projects you have coming out this year! From first creating Thomas Ligotti Online, to now having books and records coming out, I would say you are becoming a real force in the horror scene. What drew you into living a life involved with the horror genre?

Anyone who has read my pseudo-fictional, childhood retrospective, “Murmurs of a Voice Foreknown,” knows one of the primary elements that directed me towards horror: an older brother who delighted in scaring his much more sensitive sibling via nightly, creepy “true stories.” He especially exploited my fear of dolls and dummies, which was forever exacerbated by an early viewing of The Night Gallery’s production of “The Doll.” From the ages of four to nine, I had recurring doll-related nightmares almost every night. Any sensitive, young mind would be warped by these experiences, and mine was no exception. My childhood, both in the waking world and the world of dreams, was too often filled to the brim with fear, rage, and loneliness. This instability and imbalance eventually coalesced into an adult imagination that I think I can justly describe as dark and twisted.

For my money, I would say you are my favorite spoken word artist. The way you deliver words and the sort of melancholy and strange way you make the word come alive to the listener is just amazing. It would seem you just have a natural gift for verbally transmitting the nightmarish.

Wow. Thank you, Scott. I was trained as an actor from an early age and always had the knack. I wonder if I need to again credit my older brother for my initial storytelling efforts, at least in part. The nighttime, improvised stories he told me about the living Hand and Doll and the ghost of our fictional brother fed my bloated imagination to its breaking point and ultimately gave me a taste for verbally creeping out and infecting other minds with horror.

And now you have turned your attention to creating a vinyl spoken word edition of Ligotti’s The Bungalow House, which is one of my all-time favorite stories. What is it about The Bungalow House that speaks to you? Why is this work important to you? And in adapting this story, what were the challenges and what did you hope to bring to the work with your reading?

I think I understand your love of this remarkable story, Scott. It is my favorite, and when I say favorite I mean period, end of discussion. I will always feel great gratitude to Jonathan Dennison, the editor, and owner of Cadabra Records, for the opportunity to give “The Bungalow House” a beautifully produced, scored, studio-quality narrative take.

As for how “The Bungalow House” speaks to me: I feel a unique sense of being inside the story whenever I've read it. As you know, the librarian-narrator becomes obsessed with an unknown artist's work, in which a "...feeling of being in a trance in the most vile and pathetic surroundings was communicated to [the librarian] in the most powerful way, by the voice on the tape, which described a silent and secluded world where one existed in a state of abject hypnosis." This communication between librarian and artist is uncanny; he is taken with awe that "...another person shared [his] love for the icy bleakness of things." For me, Ligotti’s story is specifically and explicitly invoking the artistic relationship/connection between an author and a reader. Here is a cautionary tale regarding the limits of artistic kinship and shared obsessions, explicitly pointing out that any such connection between two separate beings must be an illusory one. Ironically, the “real world” reality of this shared kinship and obsession between author and reader is uniquely evoked by the story itself.

"The Bungalow House" simply gave me the biggest meta-fictional jolt of my life and could have—imaginatively speaking—been written about my own obsession with Ligotti's work. Coincidentally, the first time I read "The Bungalow House" I actually was working as a reference librarian—specializing in language and arts no less. To make things even weirder, I would often read and reread Ligotti’s work (and other abnormal literature) on my sometimes overlong lunch breaks. It was, in fact, an incredibly lonesome and alienating and unstable period in my life. I was single, depressed, given to periods of panic, and obsessed with the terrible, wonderful world that this mysterious author had presented to me in stories like “The Bungalow House.” Ligotti, it seemed, could have been writing from inside my own head. “The Bungalow House" is a brilliant, melancholy, psychological narrative that explores the depths of an internal, dramatic monologue while simultaneously telling an engaging story of existential yearning and despair that I—and many Ligotti readers like me—understand all too well.

As a reader, “The Bungalow House,” both in my initial 2005 effort but especially in the recent Cadabra Records recording, was by far the most demanding, difficult narration I've ever tackled. The first draft of the story that I sent off to Dennison was a complete bust, and I had to convince him that I could do better—adapting my own interpretation into his. Reading this singular tale aloud is tricky business. It’s a balancing act between where the librarian-narrator is mentally and emotionally in the opening section of the story and where he is by the end. My impulse initially was to play the character (and Dahla as well) with very little affect, which made sense to me since by the time he tells the tale, the librarian-narrator has already been through it all and has had some hard truths revealed to him. But the initial draft came across too flat and uninvolved, which is a problem if you want to keep the listener’s interest. Ultimately, I remembered Thomas Ligotti himself once describing the librarian-narrator’s voice as nervous, which put me in mind of the narrator of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” After that, it all came together, though six or seven full drafts had to be recorded before things were right.

I think the final result represents, by far, my best audio performance to date and the one of which I’m most proud. And I can credit Jonathan Dennison’s incredible artistic vision and professionalism for this.

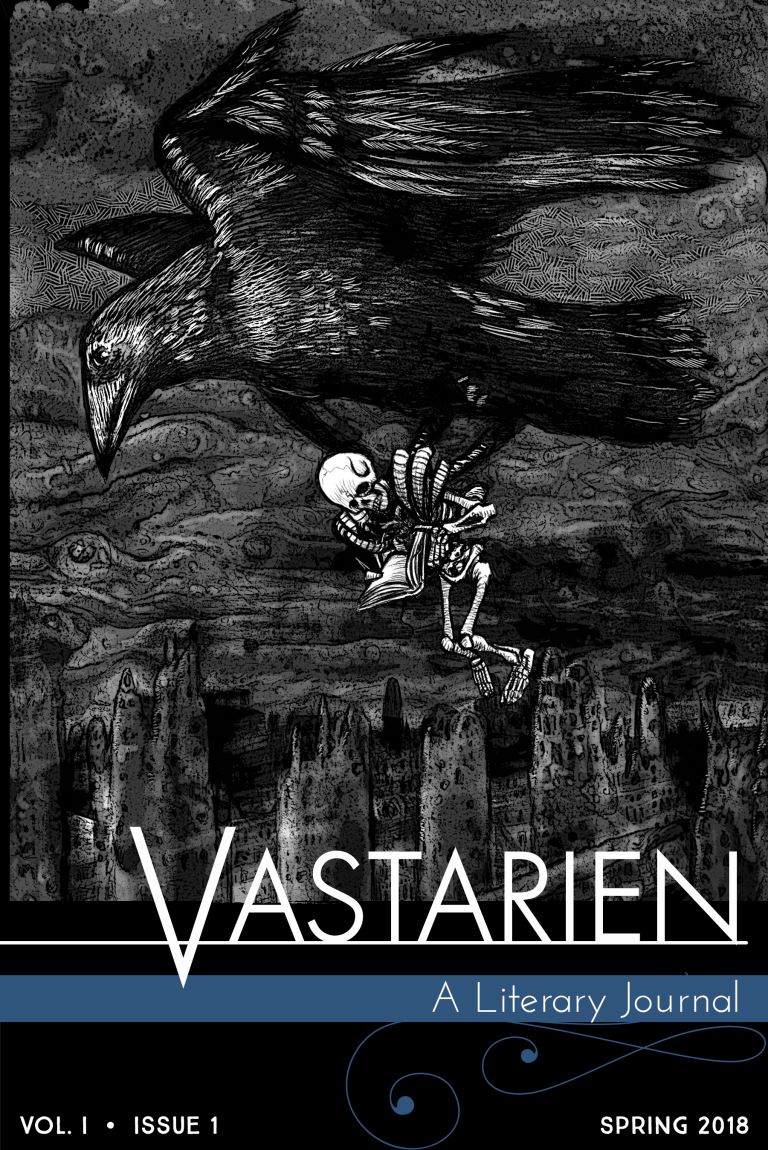

Now let’s talk about Vastarien: A Literary Journal. Vastarien is a collection of both fiction and nonfiction that it would seem looks at the horror genre through a post-Ligottian lens. A mix of both fiction and nonfiction, there are works from such authors as Christopher Slatsky, Kurt Fawver, and Jordan Krall. Topics covered in the essays include the film Eraserhead, Ligotti’s The Last Feast of Harlequin, and the films of Val Lewton. This book just seems like something I dreamed up in some fever dream. I mean, just putting the words Eraserhead and Ligotti in the table of contents together is enough to make me buy a copy! This is a book that was seemingly created for The Plutonian readers. And to top it off, there is also a rare foreword to the polish edition of Teatro Grottesco by Ligotti in there. Can you talk a little about how Vastarien: A Literary Journal came about? What were your inspirations or influences in creating this?

In August 2015, a small group of readers and writers and I came together with a common goal: to create a publication that would feature new, Ligottian/weird nonfiction, fiction, visual art, poetry, and ideas – Vastarien: A Literary Journal. Our process, from the beginning, was slow, deliberate and painstaking. Months of planning, by-law creation, and budgeting followed, leading up to the implementation of our website in May of 2016. We opened the publication for submissions for issue 1 shortly thereafter.

As time passed and final acceptances were made throughout 2016 and into 2017, the inaugural issue of Vastarien was taking shape before our eyes. The name of our journal is drawn from Thomas Ligotti’s classic story of the same title. Vastarien is a source of critical study and creative response to the corpus of Thomas Ligotti as well as associated authors and ideas. The inaugural issue is something unusually special, filled with in-depth essays, interviews, original visual art pieces, weird fiction, terrific poetry, and fascinating hybrid pieces. An interview with Thomas Ligotti and an introduction by him, neither of which have ever been presented in English, are included.

The first issue has been received well, in spite of controversy during its development (we lost multiple editors over philosophical and sometimes religious differences) and an appearance of an all-male TOC, which was not at all the case.

What are your plans for the future of Vastarien: A Literary Journal?

After a phenomenal fundraising campaign, we are set for the rest of the year and have been able to pay all our contributors pro-rates. The TOC for issue 2 has been released recently, and it should be released this June. Issue 3 should drop in September or October. We’ll see how it goes from there. A lot depends on funding and subscriptions. We want to continue paying pro-rates, but we certainly don’t want to spend months fundraising again. One way or another, Vastarien will continue, but we might move to an annual publication in 2019 and beyond rather than a quarterly release. We’ll see.

And lastly, what is in the future for Jon Padgett? Any plans or new works that we can look forward to?

Yes! Of course, you already know about “The Bungalow House” (probably dropping early June at this point), but next week my own story, “20 Simple Steps to Ventriloquism,” is being released by Cadabra Records, and I’m extremely pleased and honored by the end product. I narrated it myself and am thrilled by the “sound patterns” created by Pseudopod Co-Editor, Shawn Garrett, as well as the brilliant art by Dave Felton and Yves Tourigny (front and back cover respectively). Finally, I’m awed and humbled by the included Foreword by none other than Thomas Ligotti.

As for other upcoming publications, my novelette, The Broker of Nightmares, will be released in limited edition chapbook form by Nightscape Press later this year, and a new tale, “Yellow House,” will be published in a new anthology, Ashes & Entropy. Pseudopod is also producing an audio production of my story, “A Little Delta of Filth.” Speaking of which, my recording of “Mysterium Tremendum,” the incredible novella by Laird Barron, is set to air on Pseudopod in three parts, episodes 594-596, May 11th, 18th & 25th.

Thanks so much for taking time out of your schedule to talk with me, Scott! See you anon!